• Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D. • IDRA Newsletter • November-December 2020 •

For the past 25 years, charter schools have represented the wild west of experiments for public school reform. Originally envisioned as incubators for ideas to be used in traditional public schools, charters have grown significantly in ways that harm public schools instead. This growth impacts student achievement and the ability of public schools to keep students, families and other resources in their communities.

For the past 25 years, charter schools have represented the wild west of experiments for public school reform. Originally envisioned as incubators for ideas to be used in traditional public schools, charters have grown significantly in ways that harm public schools instead. This growth impacts student achievement and the ability of public schools to keep students, families and other resources in their communities.

Starting with 20 schools and just 2,400 students in 1995, charter school enrollment has ballooned to nearly 337,000 students in 2019-20, or about 6.1% of the Texas school population (TEA, 2020). However, because charter schools are state-funded with no local tax base, they account for a whopping 14% of state school funding – over $3.5 billion in this year (TEA, 2020a).

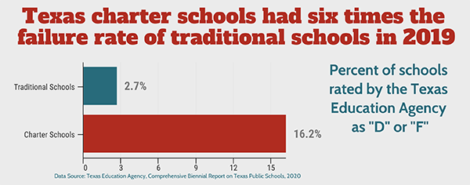

Most charter schools are privately-operated schools that receive public funding. Data show that, overall, charter schools do not outperform public schools in measures based on standardized testing, district accountability scores or student attrition rates (Burris, 2020; Han & Keefe, 2020; Johnson, 2017).

Traditional public schools that serve most Texas students need more support than ever to contend with the health, safety and academic ramifications of the pandemic. Charter school expansion compromises the education of most students, including those in failing charter schools.

Given charter schools’ mixed performance and accountability results and their high price tag, Texas must apply more scrutiny to new and existing charter schools that operate with public dollars without sufficient public accountability.

Financial Impact of Charter Schools

Charter schools cost the state an average of $1,150 more per student than neighborhood public schools (Williams, 2020), which in 2016-17 operated at just under $10,000 per student (NCES, 2019). The Education Law Center’s analysis ranks Texas at just 38th in school funding levels compared to other states (Baker, et al., 2018).

The Commissioner of Education and the State Board of Education make decisions about which and how many charter schools may exist in the state within legislative allowances. When they expand the number of charter schools, they divert state funds away from public schools. From 2000 to 2017, state funding for charter schools increased by 640% as 500 new charter campuses opened (Villanueva, 2019).

The Commissioner of Education and the State Board of Education make decisions about which and how many charter schools may exist in the state within legislative allowances. When they expand the number of charter schools, they divert state funds away from public schools. From 2000 to 2017, state funding for charter schools increased by 640% as 500 new charter campuses opened (Villanueva, 2019).

This is significant for two reasons: (1) Public schools receive funding based on their student attendance, and (2) the per-pupil funding goes to sustain the entire school district, including instruction, building facilities, teachers, counselors, staff and transportation, among other necessary educational services.

Consequently, when charter schools recruit students out of a school district, the state pays a higher price tag, and the school district loses funding for those students as well as the portion of per-pupil funding that benefits the entire district community.

This leaves school districts on the hook to serve the vast majority of students – including students who require more expensive educational services, such as special education instruction and therapies – with even fewer resources.

When one or two students leave a classroom to attend a charter school, the neighborhood school must still pay the teacher in that original classroom. The lights must stay on. The heater and air conditioner must still operate. In economic terms, charter schools have created inefficiency in the Texas public school system (Baker, 2016).

Given charter schools’ mixed performance and accountability results for students and their high price tag, Texas needs to apply more scrutiny to new and existing charter schools that operate with public dollars without sufficient public accountability.

The Texas Commissioner of Education and State Board of Education recently approved five new charter organizations to set up shop in Texas costing the state more than $14.9 million over the next five years of their operation. Those charters pull $6.8 million more from state funds than their neighboring public school districts (Williams, 2020).

In addition, the Commissioner of Education permitted a particularly controversial charter organization – IDEA Public Schools – to open 12 new campuses next year. IDEA Public Schools garnered national attention recently when several alarming financial expenditures came to light, including the former CEO’s use of $2 million in public funds to use a private jet (Carpenter, 2020). Beyond egregious expenditures, the charter organization expends much more on personnel than other public schools by paying its executives much higher salaries than is typical of public school administrators – nearly half a million dollars each – and experiences much greater teacher turnover than public schools (DeMatthews & Knight, 2020).

This extraordinary fiscal impact necessitates greater state scrutiny for charter schools to expand their current campuses and for new charter organizations to be approved to open in Texas.

Charter Schools’ Concerning Record of Segregation of Marginalized Students

Charter schools offer a rocky performance record for serving marginalized students, including Black students, Latino students, students with disabilities and English learners. Studies indicate that Texas charter schools can exacerbate racial and socioeconomic segregation within school districts by catering to and recruiting specific student groups (Heilig, et al., 2016; Miron, et al., 2010).

Distressingly, Texas charter schools serve a smaller proportion of students who receive special education services than the statewide average: 7.8% in charters compared to 10.7% in traditional public schools (TEA, 2020b). Research shows that charters push out students with disabilities by urging parents to seek other programs for their students. This practice suggests that charter schools cannot serve students with disabilities to high standards (Waitoller, 2017; Waitoller, Nguyen, & Super, 2019).

Similarly, research suggests that charter schools underserve emergent bilingual students (also referred to as English learners), either through under-enrollment or through pushing emergent bilingual students back to their home campuses, which further disrupts their learning (Heilig, et al., 2016). Texas charter school enrollment includes about 30% emergent bilingual students, higher than the state average (TEA, 2020b). But in areas with high concentrations of emergent bilingual students, researchers found that Texas charter schools served significantly lower proportions of emergent bilingual students than nearby public school campuses (Heilig, et al., 2016).

Consistent with this study, several of the new charter applicants approved in September 2020 also proposed enrolling a much smaller percentage of emergent bilingual students at their new campus than attend neighboring schools.

For instance, Clear Public Charter (which was ultimately vetoed by the State Board of Education) estimated a 12% English learner enrollment for its proposed campus in San Marcos, while a nearby school campus enrolled 69%. This suggests inequities in how students with specific instructional needs are admitted and served at charter schools.

Research also indicates a lack of reliable information on bilingual education programs and emergent bilingual student success in charter schools (Garcia & Morales, 2016). Of the nine final applicants for new charter schools considered this year, seven stated that they would offer English as a second language programs instead of bilingual education programs despite the volumes of data and research across the country showing bilingual education programs to be significantly more effective models for using the student’s home language to learn core subjects while learning English (Collier & Thomas, 2017; Robledo Montecel & Cortez, 2001).

Texas Should Evaluate New Charters with More Scrutiny

In future cycles of charter applications and amendments, the Texas Education Agency should scrutinize every charter school’s potential financial impact and segregating effects on the local school district. The state must invest funds toward public education improvements that support inclusivity, diversity and academic success for all students, rather than using precious public dollars to finance new charter schools with inconsistent records for serving some of our most vulnerable students. Instead, IDRA suggests that TEA officials and state policymakers invest in public schools to ensure safe learning environments, to close the digital divide, and to navigate the anticipated and unanticipated pandemic-related challenges of the next academic year (Latham Sikes, 2020).

Resources

Baker, B.D., Farrie, D., & Sciarra, D. (2018). Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card. New Jersey: Education Law Center.

Baker, B. D. (2016). Exploring the Consequences of Charter School Expansion in U.S. Cities. Economic Policy Institute.

Burris, C. (2020). Still Asleep at the Wheel: How the Federal Charter Schools Results in a Pileup of Fraud and Waste. New York, N.Y.: Network for Public Education.

Carpenter, J. (January 30, 2020). After backlash over $2M luxury jet, IDEA charter schools to stop spending $400K on Spurs tickets. San Antonio Express-News.

Collier, V.P., & Thomas, W.P. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 203-217.

DeMatthews, D., & Knight, D. (2020, Feb. 10). Commentary: Private Jets and Spurs Tickets? Texas Needs More Charter School Oversight. San Antonio Express-News.

Garcia, P., & Morales, P.Z. (2016). Exploring quality programs for English language learners in charter schools: A framework to guide future research. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(53).

Han, E.S., & Keefe, J. (2020). The Impact of Charter School Competition on Student Achievement of Traditional Public Schools after 25 Years: Evidence from National District-level Panel Data. Journal of School Choice, 1-39.

Heilig, J.V., Holme, J.J., LeClair, A.V., Redd, L.D., & Ward, D. (2016). Separate and unequal: The problematic segregation of special populations in charter schools relative to traditional public schools. Stanford Law & Policy Review, 27, 251.

Johnson, R. (2017). Annual Dropout and Longitudinal Graduation Rates in Texas Charter Schools, 2009-2016. Texas Public School Attrition Study, 2016-17. San Antonio: IDRA.

Latham Sikes, C.L. (2020). State Board of Education Should Vote Against All New Charter Proposals, IDRA Testimony. San Antonio: IDRA.

Miron, G., Urschel, J., Mathis, W.J., & Tornquist, E. (2010). Schools Without Diversity: Education Management Organizations, Charter Schools, and the Demographic Stratification of the American School System. Boulder and Tempe: Education and the Public Interest Center & Education Policy Research Unit.

NCES. (August 2019). Table 236.65. Current expenditure per pupil in fall enrollment in public elementary and secondary schools, by state or jurisdiction: Selected years, 1969-70 through 2016-17. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Robledo Montecel, M., & Cortez, J.D. (August 2001). Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Criteria for Exemplary Practices in Bilingual Education. IDRA Newsletter.

Texas Education Agency. (2020). Statewide summary of finances. School District State Aid Reports. Austin: TEA.

Texas Education Agency. (2020). Enrollment in Texas Public Schools 2019-20. Austin: TEA.

Texas Education Agency. (2020). Charter Locator Map, online. Austin: TEA.

Villanueva, C. (2019). Charter School Funding: A Misguided Growing State Responsibility. Every Texan.

Waitoller, F.R. (2017). Black and Latinx students with dis/abilities in charter schools: A summary of the research. Indianapolis, Ind.: Midwest & Plains Equity Assistance Center.

Waitoller, F.R., Nguyen, N., & Super, G. (2019). The irony of rigor: ‘No-Excuses’ charter schools at the intersections of race and disability. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(3), 282-298.

Williams, E. (2020). Analysis of fiscal impact of Generation 25 Charter Applicants by Ellen Williams, Attorney at Law, email correspondence.

Chloe Latham Sikes, Ph.D., is IDRA’s deputy director of policy. Comments and questions may be directed to her via e-mail at chloe.sikes@idra.org.

[©2020, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the November-December 2020 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]