Below is a log of IDRA’s policy updates for schools regarding COVID-19. We release a new policy update each week in our Learning Goes On eNews (sign up free) in English and Spanish.

Below is a log of IDRA’s policy updates for schools regarding COVID-19. We release a new policy update each week in our Learning Goes On eNews (sign up free) in English and Spanish.

Also see our new Policy Primer: Ensuring Education Equity During and After COVID-19, IDRA’s living document listing policies to preserve and promote educational equity:

- Policies to Support Learning through Summer and the 2020-21 School Year

- Budget and Policy Information for School Districts in State Legislative Sessions

- Linked Resources and Tools for Ensuring Equity in COVID-19 Responses

See the guide in Spanish, Garantizar la equidad educativa durante y después de COVID-19.

Policy News Stories

- U.S. Dept of Education Releases New COVID-19 School Guidance

- Six Ways the New COVID Relief Plan will Impact Schools

- National – New CDC Guidelines

- Texas – STAAR News

- If Teachers Controlled the Education Budget

- New COVID-19 Emergency Relief Package

- Possible Additions to the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Emergency Plan

- Biden-Harris Administration’s Education Priorities

- Effective School Assessments and Accountability that Does Not Hurt Students

- Families Share Insights on Young Emergent Bilingual Children to Inform Policy & Practice

- Reopening Presents Opportunities for Innovation and Collaboration throughout the South

- Serving English Learners During COVID-19 – School Leadership and Teacher Support

- Maintaining a Supportive School Climate

- Building Trust through Authentic Communication

- Federal Court Strikes Down Department of Education Rule Requiring Public School Districts to Give More Relief Funds to Private Schools

- Texas-focused Education Equity Groups Support Lawsuit Challenging U.S. Department of Education Rule that Shifts Relief Funds from Public Schools to Private Schools

- Family Engagement is Key to Student Safety Amidst COVID-19 Reopening

- An Equity-focused Plan for Reopening Schools Safely

- Video Spotlight on the Rules for Reopening Texas Schools

- IDRA Releases Guide to Ensuring Education Equity During and After COVID-19

- State Reopening Guidance Must Prioritize Equity

- How School Districts and Communities Can Plan Safe Learning Environments

- Schools Face Challenges to Reopening – Community Input and Supplemental Funds Are Critical

- U.S. Department of Education Affirms Intent to Exclude Undocumented Students from CARES Act Relief Funds

- COVID-19 Federal Guidance Documents Impact Schools and Communities

- IDRA Statement in Support of Black Lives

- What We are Hearing from Families, Students and Educators: Part I

- Without Intervention, COVID-19-Induced Budgetary Shortfalls Will Fall Hardest on Marginalized Students in the South

- COVID-19 Does Not Change Civil Rights Protections for Students

- IDRA Joins Counselors in Calling for COVID-19 Responses that Include Trauma-Informed Support

- COVID-19 Worsens Systemic Educational Inequity

- Public School Advocates Join Forces to Push for Emergency Funding Equity

U.S. Department of Education Announces Rules for Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Funding - Update: The CARES Act and Federal COVID-19 Actions

- Equity Concerns for English Learners in Response to COVID-19

- Students in Southern States Face Short- and Long-Term COVID-19 Challenges

- An Overview of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act

- Texas Colleges Respond to COVID-19

- Testing for Students in Texas & Equity Implications

April 16, 2021 Edition

U.S. Dept of Education Releases New COVID-19 School Guidance

This month, the U.S. Department of Education released its second handbook of recommendations for how schools across the country can safely re-open for in-person learning and meet students’ needs. The first handbook, released in March 2021, focused on the school health-related safety protocols issued by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).

The second handbook, ED COVID-19 Handbook – Roadmap to Reopening Safely and Meeting All Students’ Needs, includes recommendations on creating safe and healthy learning environments, addressing lost instructional time, and supporting educator and staff stability and well-being.

Creating Safe and Healthy Learning Environments

In addition to following physical safety protocols, the U.S. Department of Education recommends schools work to do the following to create safe and healthy learning environments.

- Meet the basic needs of students, including by providing meals to students in all educational settings during the school year and the summer. This requires understanding community needs through surveys and other family engagement processes and responding appropriately with distribution sites and plans.

- Meet the social, emotional and mental health needs of students, including those from historically-marginalized student populations who may be experiencing the unique trauma of homelessness or involvement in the foster care or juvenile legal systems. The guidance urges schools to ensure access to professionals like counselors, social workers and psychologists and to use research-based practices that focus on building relationships, strengthening family and student engagement, and creating culturally-sustaining learning environments.

- Provide all students with safe and inclusive schools that focus on developing response plans and building strong relationships, especially with chronically absent and “disengaged” students.

Addressing Lost Instructional Time

Without immediate interventions, lost instructional time could have a profound impact on many students. The handbook recommends that schools implement programs focused on accelerated instruction, tutoring and expanded learning time including out-of-school programs and summer learning.

These approaches, which can be used in combination, require teacher training in new teaching strategies, the use of data and diagnostic and formative assessments that enable teachers to respond to learning needs over time, and robust student engagement strategies. The handbook lists the characteristics of evidence-based and effective programs so that schools can evaluate and create options in their own communities.

Recommendations across programs include ensuring strong relationship-building between students and adults, creating opportunities for shared decision-making for using resources, using data that shed light on diverse measures of student access to their schools, and incorporating effective technology strategies that account for differences in access to reliable Internet connection, devices and user knowledge. The handbook also focuses on the importance of addressing long-standing educational inequities, including in school funding and the distribution of well-qualified teachers.

Supporting Educator and Staff Stability and Well-being

The handbook urges states to address the major issues related to the educator workforce that have been exacerbated by COVID-19. It notes that teacher morale has dropped during the pandemic, leading to fewer well-qualified teachers, particularly for student populations that already experienced teacher shortages or less-experienced educators including emergent bilingual students, students of color and those from families with limited incomes.

The handbook recommends strategies to recruit and retain effective teachers, including through:

- Identifying more professional development opportunities,

- Creating teacher partnership programs,

- Building a group of high-quality substitute teachers, and

- Implementing flexible teaching schedules to allow for teacher planning and collaboration time.

The handbook also stresses the importance of creating a diverse educator pipeline through grant and scholarship opportunities, teacher residency programs, and “Grow Your Own” programs that support individuals to become teachers and support students in their own communities.

Finally, the handbook stresses that teachers and other staff need the same mental health supports as others who may be experiencing trauma during COVID-19 and urges schools to create support systems that can identify and respond to teacher social, emotional and mental health needs just as they should for students.

IDRA has resources and programs to support schools with many of the recommendations described in the handbook. The IDRA EAC-South provides training and technical supports to schools and education agencies across the U.S. South, usually at no cost, and the IDRA Valued Youth Partnership is a proven cross-age tutoring program that increases attendance and student engagement. Please contact us to learn more about these programs!

March 19, 2021 Edition

Six Ways the New COVID Relief Plan will Impact Schools

Last week, President Biden signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act, the third federal relief package designed to address major financial, health and education needs caused and worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic. The law allocates almost $130 billion to K-12 schools and approximately $39 billion to colleges.

Below are six things to know about how that money will be distributed and spent.

1. Through the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), state education agencies will receive about $122 billion, which is nearly twice the funding they received from the first two stimulus packages combined. Like the first packages, at least 90% of the funds distributed to state education agencies must then be allocated to local education agencies (school districts and many charter schools) based on Title I formulae, which target funds to districts based on poverty concentration levels.

No more than 10% of the funds can be used by the state education agency for other programs. All school districts and charters that receive funds must publish, within 30 days, a plan to reopen schools and ensure continuity of education. These plans must be open for public comment (unless a similar plan has already been produced by the district or charter).

2. School districts and charter schools that receive funding must use at least 20% of the funds to address learning loss (or instruction disruption). This includes evidence-based strategies like summer learning opportunities, extended-day and extended-year programs, and afterschool programs. These funds must be used to support students’ emotional, social and academic needs with a focus on students who were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic. State education agencies also must use at least 5% of their ESSER funds to address learning loss.

3. The remaining funds received by school districts and charter schools can be used for a wide range of purposes, including the following:

- Providing mental health supports, including through community schools;

- Implementing any activity authorized by other major federal education laws, including the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA);

- Purchasing technology supports and devices;

- Implementing a valid and reliable assessment system to track student learning;

- Providing facilities upgrades and sanitation services in schools; and

- Providing information and assistance to families on how they can support their students while they learn virtually.

4. Private schools will receive $2.75 billion through the Emergency Assistance to Non-Public Schools Program distributed by governors. This program is different from the equitable services requirement that required public schools to provide services to private school students and was debated following the passage of the CARES Act.

5. Colleges must use at least 50% of their funds to provide emergency financial aid grants directly to students in a manner similar to the first emergency relief packages.

6. States and school districts that receive emergency relief funding must adhere to “maintenance of effort” and “maintenance of equity” requirements. Typically, recipients of federal funds must follow maintenance of effort provisions, which prohibit states from unnecessarily reducing their support for public schools as compared to previous years. With this new law, states must maintain their previous financial support of elementary, secondary and postsecondary schools (colleges and universities), including their funding of state need-based financial aid for postsecondary students, unless they receive a waiver from the U.S. Department of Education.

Additionally, states, school districts and charter schools that receive emergency relief funds must follow maintenance of equity provisions that are designed to ensure that any reductions in school funding due to revenue shortfalls do not disproportionately impact schools and districts with high concentrations of poverty. These provisions provide that, in 2022-23:

- States cannot reduce per-pupil funding in high-need school districts* more than the average reduction for school districts across the state;

- States cannot reduce per-pupil funding for the highest-poverty school districts** below the amount of per-pupil funding provided to those districts in fiscal year 2019; and

- Most school districts and charters cannot reduce per-pupil funding or staff in high-poverty schools*** in a manner that disproportionately impacts those schools compared to others in the district.

Other provisions of the Act will impact students and schools, including the expansion of COVID-19 vaccination and testing programs. The expansion of child tax credits, which will come in the form of monthly payments for qualifying families with children, could drastically reduce child poverty and improve outcomes for students and families across the country (Parolin, et al., 2021).

As with each COVID-19 relief package and all education resources, the monies from the American Rescue Plan Act will be most impactful if they are distributed, targeted and tracked in ways that promote equity and focus on historically-marginalized students, including students of color, emergent bilingual students, and students from families with limited incomes.

The state must allocate the funds to school districts within 60 days of the state receiving them. It is crucial that community engagement plays a role in the process to decide how funds are used. To stay involved and up-to-date on state policymaking processes and advocacy opportunities, follow IDRA on social media and sign up for our community engagement resources and advocacy updates Texas Education CAFE Advocacy Network.

Notes

* According to the American Rescue Plan Act, high-need school districts are those that “(A) in rank order, have the highest percentages of economically disadvantaged students in the state, on the basis of the most recent satisfactory data available from the U.S. Department of Commerce (or, for local education agencies for which no such data are available, such other data as the U.S. Secretary of Education determines are satisfactory); and (B) collectively serve not less than 50% of the state’s total enrollment of students served by all local educational agencies in the state.”

** According to the American Rescue Plan Act, highest-poverty school districts include those that “(A) in rank order, have the highest percentages of economically disadvantaged students in the state, on the basis of the most recent satisfactory data available from the U.S. Department of Commerce (or, for local educational agencies for which no such data are available, such other data as the U.S. Secretary of Education determines are satisfactory); and (B) collectively serve not less than 20% of the state’s total enrollment of students served by all local education agencies in the State.”

*** According to the American Rescue Plan Act, high-poverty schools are those in the “highest quartile of schools served by such local educational agency based on the percentage of economically disadvantaged students served, as determined by the state…”

Parolin, Z., Collyer, S., Curran, M.A., & Wimer, C. (2021). The Potential Poverty Reduction Effect of the American Rescue Plan, Poverty & Social Policy Fact Sheet. Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Columbia University.

February 12, 2021 Edition

New CDC Guidelines

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued new guidelines today for how schools should operate safely during the pandemic, being careful to note they are not mandating that schools reopen. The “operational strategy” released today includes recommendations for determining the safest learning options for schools (fully in-person, hybrid, fully virtual) based on a four-tier scale that considers the rates of disease transmission in the community.

Additionally, the CDC recommends schools adopt five “layered mitigation” strategies with research-based practices which, in combination, should help to ensure student and staff safety in schools:

- Universal and correct use of masks, which should be required for all students and staff;

- Physical distancing of at least six feet, with classes reduced to smaller groups of students, or “pods,” to ensure separation;

- Hand washing and other respiratory infection prevention procedures;

- Frequently and thoroughly cleaning school facilities and ensuring effective ventilation systems; and

- Contact tracing protocols that allow for rapid responses to COVID-19 outbreaks.

Finally, the CDC encouraged states and schools to prioritize teachers and other school staff for vaccinations (though the CDC maintains that not all teachers must be vaccinated for schools to reopen safely). Additionally, schools should facilitate testing and ensure that reopening plans take into account the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on communities of color.

The CDC strategies will be supplemented by a scientific brief by the CDC and a multi-volume handbook with school re-opening and safety recommendations issued by the U.S. Department of Education.

Texas – STAAR News

Texas Education Commissioner Morath spoke with the Texas Tribune about the state of education during the pandemic. He noted that while the state’s assessment, STAAR, would be conducted in-person in order to gather data about student learning, a virtual option would not be offered, and families would not be required to bring their children into schools for testing.

He also shared his thoughts on the best ways to address educational inequities for students of color, including “increasing the rigor of the content students learn, supporting teachers’ professional growth and increasing the length of the school year.” He did not answer whether school funding would be cut due to COVID-19-related dips in student attendance – a concern shared by many school districts and advocates.

See IDRA’s Recommendations for the 87th Legislative Session, including recommendations to extend hold harmless provisions and protect funding for public schools.

If Teachers Controlled the Education Budget

In IDRA’s course at Texas A&M University-Commerce, we asked a group of current and former educators what they would do if they had power over the state’s budget and could direct funds to make the greatest impact for our education system.

Below is what they said and a way for you to share your ideas.

“Oh, how nice this would be: unlimited funding. The power to pass any budget? Wow… I would fund training. This is an all-around training focus. Yes, training for technology that we so desperately needed when schools went online, but also training for career and further education resources along with the salary so that we can fund more counselors.”

“Teachers need resources in their classrooms to be successful. Many teachers do not have adequate resources to teach in the manner they need… Many teachers and students who do have technology do not have the proper training needed to use the technology in the most effective manner. Offering training for teachers and students could benefit everyone in the school community.”

“Family and community engagement opportunities are a great way to build the partnership between the school district, and the community in turn can help the success of the overall school community. By providing resources and training for families, the school district would be gaining the support and trust of those families within the community.”

“More funding for mental health, including SEL [social emotional learning]. Children and adults need to express their concerns.”

“I would increase salaries across-the-board for the industry of education. This industry should be competitive as a necessary and high-priority industry for attracting and retaining valuable members. It would be great if this industry could be one that people move toward because of the good pay.”

“Students, teachers and staff across the state should be given and/or have access to current technologies to help them complete their job requirements. This could work even better if individuals could be given a fund or allocation to spend this money on their specific technology needs. For example, teachers each year should be given an allotment of a minimum of $1,000 to spend on their technology needs for the school year. These funds would help to increase the potential for higher engagement and new instructional techniques where students would greatly benefit. This would need to be a reoccurring fund to keep up with the changes in advancements in technologies.”

“I would spend a significant amount of funding the overall infrastructure for new or renovated campuses and facilities across the state. Campuses are not able to keep up with the advances in technology and other resources that are currently available, and the system is in need of costly repairs just to keep the buildings open. Funding options directed specifically toward the infrastructure of districts could help speed up this process and take the burden off local communities.”

“A lack of broadband connectivity has widened the equity gap throughout the state. Training teachers to properly utilize technology will support the teachers, and students will benefit from a more enriched instructional experience. Working in a safe and healthy environment helps one focus on quality instruction and bridge the socio-emotional support that all students crave: person-to-person interaction.”

“It is well past time to get creative when it comes to fostering active family engagement, especially in critically impacted communities. Investing in schools goes beyond updating infrastructure and resources and moves into the realm of outreach. Would it be easier to get parents in buildings, in classrooms, involved if schools had community use laundry facilities? Or a day care? Or free family breakfast? What if schools also invested in parents and were able to offer a variety of helpful and fun night classes related to the GED or English language instruction or cooking classes or guitar lessons? What if schools also hosted various well-funded and intentionally advertised cultural events and community celebrations?”

“In a world that requires digitally-powered education, our education system is behind the eight ball when it comes to technology. The divide between the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’ is appalling. But even more appalling is the fact that the technology in the hands of the ‘haves’ is outdated and, in most cases, antiquated. So, the benchmark we are using for a best-case scenario of bridging the digital divide is subpar at best. Educational technology needs an overhaul statewide, at every school, at every level.”

“It’s time schools were staffed in ways that make sense. Students deserve timely and thoughtful feedback along with true data-driven instruction with personalized reteach and enrichment opportunities. At the same time, teachers deserve to have full lives outside of school. Funding could significantly reduce caseloads of teachers and mental health personnel to ensure that students get what they need while their supporting adults don’t struggle with feeling overwhelmed to the point of inadequacy.”

“My first priority will be to establish a comprehensive plan to support school efforts to establish and to provide for a safe, conducive learning environment for all our students. This means [personal protective] equipment (PPE), testing, contact tracing and vaccination. If students are not safe, it is harder for students to learn. Children whose learning has been disrupted from areas that are especially hit hard by the pandemic, like Laredo, Texas, or Los Angeles, are poised to observe significant learning losses. Getting a handle on the pandemic should, therefore, be a top priority.”

In IDRA’s course through Texas A&M University-Commerce, we are supporting the development of scholar/educator advocates who can understand and influence state policymaking. These students are helping us to examine and refine our own policy positions and how they impact schools.

Do you have ideas for how you would spend funds on public schools? Share them with the hashtag: #WhatSchoolsNeed.

January 21, 2021 Edition

Federal Education Policy Update

by Morgan Craven, J.D.

This week’s inauguration marked the official transition of power to President Biden and the beginning of new priorities in the U.S. Department of Education. Below we provide updates in three critical areas of federal education policy:

- the impacts of the most recent COVID-19 emergency relief package;

- likely additions to the government’s COVID-19 emergency response plan; and

- the education priorities put forth by the new Biden-Harris administration.

New COVID-19 Emergency Relief Package

In December 2020 the U.S. Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which includes the second COVID-19 emergency relief package. The CARES Act in March 2020 provided $13 billion to K-12 schools and $14 billion to institutions of higher education. The new package allocates education funds for distribution through governors, state education agencies, and institutions of higher education. The major education-related portions of the aid package include the following.

In December 2020 the U.S. Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which includes the second COVID-19 emergency relief package. The CARES Act in March 2020 provided $13 billion to K-12 schools and $14 billion to institutions of higher education. The new package allocates education funds for distribution through governors, state education agencies, and institutions of higher education. The major education-related portions of the aid package include the following.

- About $54 billion for K-12 schools through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSER), most of which will be distributed to local education agencies (e.g., school districts) by each state’s education agency. This funding will be distributed in amounts proportional to districts’ Title I funding, which is based on the proportion of students from families with limited incomes.

Three new allowable expenses for the K-12 funds were added to those enumerated in the CARES Act. Schools can now use emergency funds to improve and update facilities to reduce the spread of the virus and to improve air quality in school buildings. They also can use the funds to address student learning loss, including costs associated with administering assessments, providing individualized instruction, implementing evidence-based strategies to meet student needs, providing assistance to families to support students during distance learning, and tracking student attendance and engagement in distance learning.

- About $4 billion for governors to spend on education priorities in their states, including emergency support for school districts, colleges and universities, and other education agencies most impacted by COVID-19. This fund includes up to $2.75 billion for distribution to private schools.

- Nearly $23 billion for colleges and universities, which must distribute at least half of funds directly to students in the form of individual emergency aid.

Possible Additions to the Federal Government’s COVID-19 Emergency Plan

Students and schools need far more federal support than the CARES Act and second relief package provide. President Biden has already released his $1.9 trillion “American Rescue Plan,” detailing what immediate COVID-19 and long-term health and economic recovery should look like.

Students and schools need far more federal support than the CARES Act and second relief package provide. President Biden has already released his $1.9 trillion “American Rescue Plan,” detailing what immediate COVID-19 and long-term health and economic recovery should look like.

One of President Biden’s major priorities is to re-open the majority of K-12 schools in the first 100 days of his term, including through a national program to distribute the COVID-19 vaccine, provide paid sick leave, address rampant health disparities, and ensure regular testing protocols in schools.

He also proposes to allocate $170 billion to K-12 schools and colleges, including $130 billion for safe school reopening. These funds would be used to support reduced class sizes, implement cleaning and ventilation upgrades, hire counselors and nurses, provide summer learning supports, expand community schools, prevent state cuts to pre-K programs, and address the digital divide, among other uses.

A portion of these funds also would be used for “COVID-19 Educational Equity Challenge Grants,” which will support governmental partnerships with teachers, families and others “to advance equity- and evidence-based policies to respond to COVID-related educational challenges and give all students the support they need to succeed.” For information about equity-focused resources for schools, families, and other education-focused groups, see the IDRA EAC-South website.

The proposed American Rescue Plan also includes $35 billion for colleges, including up to $1,700 for direct financial assistance to individual students and $5 billion for governors to allocate to education programs and students hardest hit by COVID-19.

Biden-Harris Administration’s Education Priorities

President Biden’s American Rescue Plan is a COVID-19-focused supplement to the education agenda from his campaign, which includes proposals to triple Title I funding for schools that serve high concentrations of students from families with limited incomes; makes major investments in institutions of higher education particularly community colleges, minority-serving institutions, and historically Black colleges and universities; and takes steps like increasing the numbers of counselors and other health professionals in schools to tackle practices that create harmful school climates.

President Biden’s American Rescue Plan is a COVID-19-focused supplement to the education agenda from his campaign, which includes proposals to triple Title I funding for schools that serve high concentrations of students from families with limited incomes; makes major investments in institutions of higher education particularly community colleges, minority-serving institutions, and historically Black colleges and universities; and takes steps like increasing the numbers of counselors and other health professionals in schools to tackle practices that create harmful school climates.

While his initial campaign platform lacked certain critical elements that many education equity advocates hoped for (including how to improve educational opportunities for English learners), subsequent policy statements indicate a broader education agenda that many hope will be responsive to both COVID-19 needs and the systemic inequities felt most by historically-marginalized students. To execute this agenda, President Biden nominated Dr. Miguel Cardona for U.S. Secretary of Education.

Among its other duties, the U.S. Department of Education must fulfill its obligation to protect students’ civil rights. There is much to do to implement needed reforms and reverse policies of the last four years that compromised equal access to education for millions of students, particularly students of color, LGBTQ students, English learners, immigrant students and many others.

For more information about IDRA’s federal education policy recommendations, please see our letter to the Biden-Harris transition team and our recommendations for federal COVID-19 relief funding, or contact Morgan Craven, J.D., IDRA’s National Director of Policy, Advocacy and Community Engagement at morgan.craven@idra.org.

December 10, 2020 Edition

Effective School Assessments and Accountability that Does Not Hurt Students

by Dr. Chloe Latham Sikes

Accurate, valid data on student learning provide a crucial metric for how students, educators, and school leadership have navigated learning and instruction during any normal school year. While there is much work to be done to improve our system of assessing learning, the data we get can help to ensure that no group of students is denied equal access to education.

Accurate, valid data on student learning provide a crucial metric for how students, educators, and school leadership have navigated learning and instruction during any normal school year. While there is much work to be done to improve our system of assessing learning, the data we get can help to ensure that no group of students is denied equal access to education.

COVID-19 has presented additional challenges to assessing teaching and learning, requiring states across the country to immediately adjust their testing and accountability systems.

Texas uses the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR) as the standardized test to assess Texas students’ academic performance. STAAR scores for each school campus and across school districts are heavily weighted in the public school accountability system to rate how districts and schools are performing.

STAAR provides the main statewide benchmark for student academic performance and progress. While any single test is an imperfect measure of students’ comprehensive learning progress, data that can be compared across years and student groups remains important for assessing students’ educational opportunities.

Where We Stand for the Upcoming Texas Legislative Session

In light of an increasingly widening learning gap and the importance of quality, valid data, IDRA supports canceling the full STAAR in the spring of 2021 in favor of an interim STAAR assessment. This interim assessment should be given to a representative sample of students based on the same methodology used by National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) across an expanded testing time between January and April of 2021.

All interim assessments should be used as formative assessments for diagnostic purposes to determine how students are learning. In addition to sample test data, opportunity-to-learn metrics can provide a more holistic picture of students’ learning and schools’ educational environments this year.

We similarly support reducing the number of state end-of-course exams in Texas by eliminating that English II and U.S. History exams that are not required by federal law (ESSA).

With these changes to student performance data, we urge suspension of high-stakes consequences for students associated with STAAR performance, such as grade promotion and high school graduation. School accountability must not harm students now or ever.

IDRA also has been urging that no A-F public school accountability ratings be issued, similar to spring 2020, due to a lack of normal assessment data and drastic changes in schools’ enrollment this year. The Texas Education Agency announced today that A-F ratings would be paused for 2020-21 school year.

See IDRA’s Legislative Priorities Factsheet: Grow and Sustain School District Health (in English & Spanish)

Why We Need Formative Assessments without High-stakes Accountability Sanctions

The global COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible for schools to properly administer the STAAR exam in the spring of 2020. Alarmingly, the COVID-19 virus infection rates have worsened since the first shutdowns last spring and continue to trend upward in Texas. Even with adjustments and additional resources, administering the STAAR remains extremely challenging.

Formative assessments are tests, assignments, or projects that measure how a student is learning content and where they need additional support. Summative assessments –such as the STAAR – are designed to measure how much a student has learned of specific content at the time of the test. They do not necessarily indicate new opportunities to support student learning.

Many students attend school remotely or in hybrid learning environments (partially in-person, partially online). Schools have lost contact with an estimated 250,000 Texas students this school year. We already know that students are struggling to maintain their grades this year, especially remote learners who are of color and in lower-income households strapped for resources.

Learn more at IDRA’s Education Policy Website on Growing and Sustaining Healthy School Districts

What Else We Should Consider as Metrics for Student and School Success

To paint a fuller picture of how students are faring in schools, IDRA advocates the collection of opportunity-to-learn metrics for the 2020-21 school year that are complimentary to interim testing. These metrics would help school districts address chronic absenteeism prevalent in schools during the pandemic. Metrics include:

- State report on the rates of in-person vs. remote student attendance disaggregated by special student population and consideration for chronic absenteeism;

- State report on the number of students “disengaged” (not completing assignments) in the 2020-21 school year;

- State report on educational digital divide (number of students without connectivity and/or devices);

- State report on forms of distance learning provided by school districts in 2020-21;

- State report on teacher preparation methods in distance learning instruction and teacher persistence throughout 2020-21 (including substitute teacher rates);

- COVID-19 positivity rate monthly average for districts’ counties this school year (since August 2020);

- Discipline data by instructional environment (virtual, hybrid, etc.) and according to discretionary discipline codes; and

- Data on the difference in attendance rates and enrollment averages for school campuses between the 2020-21 year and each of the three preceding school years (2017-18 to 2019-20, pre-pandemic levels).

Student assessment should be meaningful and informative and not lead to punitive consequences for students’ learning and graduation. More holistic metrics of students’ opportunities-to-learn can provide a complementary picture to how students have fared this year and how schools can support them.

November 19, 2020 Edition

Families Share Insights on Young Emergent Bilingual Children to Inform Policy & Practice

For many years, IDRA has hosted Mesas Comunitarias, or community roundtables, to bring together families to discuss pressing education issues facing their students and schools. These gatherings are part of IDRA’s community-centered approach to policymaking, which supports local advocacy work and ensures that communities with lived expertise are partners in state-level policy efforts.

At a virtual roundtable event this week, IDRA brought together community members from across Texas to discuss opportunities to support young emergent bilingual (English learner) students and their families.

Previous Mesas Comunitarias hosted by IDRA focused on the impact of state policies like Texas’ House Bill 5. This law, passed in 2013, changed graduation requirements for students across the state, potentially putting students at a disadvantage in their education attainment process. Through a previous roundtable focused on this law, community partners in the lower Rio Grande Valley identified opportunities to advocate for college readiness and higher graduation standards for the students in their community.

Like previous events, the purpose of the most recent Mesa Comunitaria was to identify opportunities for policy change, driven by families across Texas. The session, held primarily in Spanish with translation provided throughout, focused specifically on the experiences of families of young emergent bilingual students and aimed to identify family advocates for a statewide advocacy effort called the Early Childhood English Learner Initiative.*

Family advocate partners will help to advance the policy agenda of the initiative and will provide invaluable perspectives and expertise to ensure equitable and excellent educational opportunities for young emergent bilingual students.

Some of the most impactful input from the family participants includes the following:

Parents of emergent bilingual students believe their children should be bilingual not only to be competitive in a globalizing workforce, but because their language is part of their cultural identity and connects them to their roots. Many participants noted that bilingualism connects their children to cultural identity and wisdom.

Participants emphasized the power in collective action and advocacy for young students, acknowledging the importance of advocating for policy change together.

Families want more information on the different types of bilingual education programs that are offered in schools. This need points to a concerning lack of information from the state education agency and local school districts about even basic programs for young emergent bilingual students.

Participants have concerns about how dual language education is implemented in their districts. Though recent school funding policies provided for a small increase in funding for dual language programs, families continue to see problems with implementation of these programs for their students.

These insights were invaluable to connect participants and reveal common challenges families and young emergent bilingual students face. Importantly, the information will influence local and state-level efforts to change educational policy and practice.

IDRA will continue to host regional Mesas Comunitarias over the next several months. We encourage families from across the state to participate to help to ensure educational policies and practices at all levels are driven by the students and families impacted by them.

For more information about participating in a Mesa Comunitaria or partnering as a family advocate in the Early Childhood English Learner Initiative, contact IDRA’s Deputy Director of Policy, Dr. Chloe Latham Sikes at chloe.sikes@idra.org.

*The Early Childhood English Learner initiative is funded through the generous support of Philanthropy Advocates with the leadership of Texans Care for Children and in partnership with IDRA and other advocacy organizations and experts. IDRA serves as a steering committee co-leader with Texans Care for Children; Philanthropy Advocates; Dr. Dina Castro, UNT Denton; and Texas Association for the Education of Young Children (TxAEYC).

October 14, 2020 Edition

Reopening Presents Opportunities for Innovation and Collaboration throughout the South

Across the country, students, families and school communities face numerous challenges to safely, effectively and equitably reopening schools. To meet these challenges, school districts across the South have developed innovative and collaborative strategies that may serve as examples to school districts across the region.

Increasing Engagement with Communities to Provide Support for Families

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated longstanding disparities in engagement between schools and communities. Those that have focused on engagement use a number of strategies to not only understand the needs of their communities but also to provide corresponding support to meet those needs.

For example, the Miami-Dade County Public Schools in Florida conducted a survey of over 250,000 families and incorporated the feedback from those surveys into a plan that prioritized a variety of supports to help parents navigate the start of the school year. The plan featured a week of welcome, a parent academy, and resources focused on topics relevant to resuming learning, including navigating student and parent portals, accessing resources for mental and social-emotional wellness, and building organization and study skills. In addition, the district developed a range of communication tools to disseminate resources to parents and families, including the use of a Distance Learning Help Desk, a K-12 Help Desk, and a Mental Health Hotline.

Similarly, the Houston Independent School District (ISD) created a plan to engage parents based on the most common mediums that parents use. The plan uses a combination of social media, news media, guides, blog posts, in-person and virtual meetings, and the district’s website to communicate with parents.

Increasing Engagement to Support Disengaged and Disconnected Students and Families

As a result of the pandemic, schools were forced to rapidly switch to remote instruction and have been working to find and engage students from a distance. To address this challenge, districts have had to find ways to track students who have become disengaged and to provide resources to staff and educators to work together to support those students.

For example, San Antonio ISD launched a student interaction tracker app that helps the district track disengaged students. The app documents interactions between teachers, support staff and students as well as whether or not students are completing assignments. It allows all of the teachers and staff who work with an individual student to stay up to speed on their engagement and progress and when they need additional support or specific help.

School districts also are working to address additional resource gaps that create disconnections with students and families. For example, Guilford County Schools in North Carolina took several deliberate steps to expand access for families. The district purchased devices for nearly every student, teacher and instructional staff member. It also is addressing internet infrastructure by deploying 125 “smart buses” in high-need communities to help bridge the digital divide. In addition, the district is working with city officials in High Point to jointly identify more locations with city-owned and managed Wi-Fi that can be accessible to students and families. The district offers free-of-cost learning centers in targeted areas of the county for students to participate in remote learning as well.

These are but a few of the examples of innovative strategies being undertaken across the South to address the challenges presented by COVID-19. To ensure equitable outcomes for students this fall, education leaders should continue looking to their contemporaries across the region and adapt these strategies for the benefit of all students and families that they serve.

October 8, 2020 Edition

Serving English Learners During COVID-19 – School Leadership and Teacher Support

As schools work to balance virtual and in-person instruction, English learners, their families and teachers face unique challenges in access, teaching and learning. A number of years ago, IDRA conducted a national study to identify the practices in schools that enable students to grow academically and socially in their native language as well as English. The study resulted in IDRA’s rubric, Good Schools and Classrooms for Children Learning English, to help people in schools and communities evaluate five dimensions that are necessary for success: school indicators, student outcomes, leadership, support, and programmatic and instructional practices.

Those dimensions are just as important today in virtual settings. This issue of Learning Goes On provides recommendations for the dimensions related to school leadership and support.

Supporting Excellent Programs for English Learners

In-person student engagement with teachers is ideal for listening, speaking and other social interactions that are critical parts of language development. But virtual platforms and limited in-person engagement caused by COVID-19 precautions hinders such engagement.

Recommendations for supporting English learners’ social and academic development include:

- Schools can provide increased instruction, tutoring and one-on-one support time for English learners. These additional supports should rely on virtual adaptations of best practices for English learner programs (IDRA, 2015; Robledo Montecel & Cortez, 2001).

- As schools phase-in bringing students back into classrooms, educators should focus first on students who most need in-person support, including English learners.

- State and local education agencies should provide professional development for teachers focused on culturally-sustaining instruction and other research-based ways to support English learners.

Facing Teaching and Assessment Challenges for Schools and Families

Many teachers and families report difficulty and confusion with teaching and assessment systems for English learners. Some families say they are unsure if their child(ren) even passed courses from the last school year after COVID-19 closures. Some districts report that, early in this school year, significant numbers of students are already struggling with assessments.

Recommendations for more effecting teaching and learning systems for English learners include:

- School districts should use frequent, formative virtual and in-person assessments that enable teachers and families to evaluate learning over time and respond immediately to student needs.

- School districts should provide families with accessible translation services and translated classroom materials, virtual platforms, instructions, assessment and curriculum information, and updates so that parents who do not speak English can support their students and connect with teachers.

- State and local education agencies should create special virtual platforms or similar non-virtual support systems and hire dedicated personnel to provide training and resources to support teachers and English learner students and families.

Addressing Digital Divide Challenges

Many families face digital divide challenges in three major areas: connectivity, access to devices and user knowledge of specific technologies. The digital divide deeply impacts communities of color, including families of English learners, and communities with lower incomes and wealth disproportionately.

Additionally, some English learners may be, or have family members who are, immigrants. Immigrant families, particularly Latino-led immigrant families, are less connected than other families with limited incomes and are more likely to have mobile-only internet access (Rideout & Katz, 2016). Some families report receiving devices, like tablets, from their schools, but not enough for each child to use.

Some solutions to these access issues include:

- State legislatures should ensure affordable internet access for all communities, recognizing connectivity as a public utility necessary for school, work and other types of engagement.

- School districts and local government agencies should ensure access to devices through community spaces and identify ways to provide devices to each student in a family.

- Families can work with their schools and local non-profit organizations to create community-based connections that encourage technology mentoring between college students/professionals and families.

Building Family-School Engagement

Even without the digital divide, systemic shortcomings in how many schools engaged with families before COVID-19 were magnified in recent months and prevented important communication from happening as schools reopen. Weeks after schools began instruction for the fall, some school districts still report lost contact with students and families. And, data show that schools are less likely to have consistent contact with Black and Latino families, including families of English learners, even controlling for connectivity issues.

To address these challenges, school districts should do the following:

- Increase the number of family support specialists in schools who can communicate with parents in the district. Ensure staff have the capacity to send all messages, updates and other communications to families in multiple languages.

- Do not enforce punitive truancy measures. Retrain truancy officers or shift funds for those positions to bilingual family support specialists, counselors, social workers and other well-trained professionals who can meaningfully engage with families.

- Increase staff and budgets for school district family engagement departments.

- Expand the community schools approach to build connections between families, community-based organizations and schools.

- Assume a virtual extension of the protections in Plyler v. Doe. Schools should not do anything, including through online platforms, to deny or chill access to schools for immigrant students or families. Schools should not penalize students who do not feel comfortable turning on video cameras that may show their homes or families.

- Expand ethnic studies course offerings, training in culturally-sustaining pedagogy, and access to curricula that promotes safe, supportive and welcoming schools for all families.

To learn more about IDRA’s policy recommendations, check out our Policy, Advocacy, and Community Engagement website and our COVID-19 policy primer, Ensuring Education Equity During and After COVID-19.

And see our Web-based Technical Assistance Package on Family Engagement by the IDRA EAC-South.

References

IDRA. (2015). A Framework for Effective Instruction of Secondary English Language Learners. San Antonio, Texas: Intercultural Development Research Association.

Rideout, V., & Katz, V. (2019). Opportunity for all? Technology and learning in lower-income families. A report of the Families and Media Project. New York: The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop.

Robledo Montecel, M., & Cortez, J.D. (August 2001). Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Criteria for Exemplary Practices in Bilingual Education, IDRA Newsletter.

September 24, 2020 Edition

Maintaining a Supportive School Climate

A positive school climate is crucially important to school success. It affects attendance, engagement, learning and even graduation rates.

Yale University researchers stated in a recent article: “Schools with positive climates enjoy not only better academic outcomes, but also a host of social and emotional outcomes, such as reduced bullying, greater engagement and higher school-satisfaction ratings. Teachers, too, benefit from a positive school climate, with studies showing less stress and burnout and greater job satisfaction.”

But educators have never had to tend to school climates in a virtual world at the scale COVID-19 caused. Below are ways that school districts can ensure safe and supportive campus climates for students, teachers, staff and families during this pandemic.

1. Train adults, students and families on recognizing and responding to trauma, basic needs and COVID-related stress

Teachers and school staff need to be equipped to recognize issues like mental health crises, food insecurity or stress that students and adults may be experiencing. School districts can create resource databases and encourage community-school partnerships to help address the needs that arise. See information from IDRA on how school districts should develop support systems for students’ academic, social and emotional needs.

2. Prohibit suspensions, alternative school placements, and other inappropriate and harmful discipline practices that remove students from in-person and virtual classroom settings

These practices are ineffective and unfairly target students of color, students with disabilities, and LGBTQ youth under normal circumstances. They are especially inappropriate during the pandemic when many adults and students are in challenging situations that impact their ability to come to school fully engaged and ready to teach and learn. See information from IDRA on how school districts should face pandemic-related issues in school.

3. Protect the free speech rights guaranteed to students by the U.S. Constitution

As the U.S. Supreme Court stated in its 1969 decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, “students do not shed their rights to freedom and expression at the schoolhouse gate.” Likewise, students participating in instruction from home should have their right of free speech protected and should not be punished for expressions, including perceived dress code violations, that do not disrupt teaching and learning processes. See information from IDRA on student’s free speech rights.

4. Do not use punitive measures to enforce COVID-19 public health recommendations

Some school districts have decided to harshly punish students for behaviors like sneezing, coughing and violating social distancing rules. Harsh punishments for this conduct are a poor deterrent and have harmful – and potentially discriminatory – impacts on the students who become criminalized as well as impacts on the entire campus community.

Schools should focus instead on positive methods to encourage compliance with public health guidelines, including providing personal protective equipment, teaching students about COVID-19 and the science behind infectious disease spread, and creative incentive systems that reward students for supporting and complying with public health protocols. See information from IDRA on how school districts should face pandemic-related issues in school.

5. Give students time to check in with their peers

Having designated time for check-ins can help students to feel less socially isolated and more aware of their feelings and needs. It can help teachers identify the supports students need and maintain safe classrooms that are centered on preventative and effective care. See information from IDRA on how school districts should develop support systems for students’ academic, social and emotional needs.

6. Protect the rights of immigrant students and families

Protections guaranteed to immigrant students and students from immigrant families by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plyler v. Doe extend to students at home during the time of virtual learning. Schools should not have any policies, procedures or other requirements for online learning spaces that threaten the safety of students or families or that limit their ability to participate in school. For more information on how schools can protect and welcome immigrant students, see IDRA’s welcoming immigrant student’s infographic.

7. Do not send police officers, including school resource officers (SROs), to students’ homes for discipline purposes, attendance compliance procedures or other interactions

If students or families need welfare checks, these should not be done by law enforcement officers, but by social workers, counselors or family support specialists who are trained to address needs without taking punitive measures. For more information on how school districts should engage school resource officers, see IDRA’s School Policing Resources.

September 17, 2020 Edition

Building Trust through Authentic Communication

A recent nationwide survey about reopening schools this fall found that families with limited economic resources and Black or Hispanic families were much less likely than white or wealthy families to believe that educators could keep schools safe. These differences in attitudes may be attributed in part to differences in how educators communicate with families.

Negative interactions with schools clearly diminish the trust that parents and caregivers have in schools. When most of a school’s communication tactics rely on one-way communication and focus on disseminating information, the school misses opportunities to build relationships with students’ families.

Activities like sending fliers home with students, creating promotional videos, sending mass e-mails and leading static webinars or presentations – while needed – are not examples of authentic communication between schools and families. These methods do not allow for meaningful feedback from parents and caregivers. Likewise, when communicating information about student progress, it is not enough to merely post such things as grades on a parent portal on the district’s website.

As students are physically and socially disconnected from school campuses via online instruction, caregivers and teachers need authentic dialogue more urgently.

One Southern district, served by the IDRA EAC-South, discovered a deeper issue when leaders collected data intending to identify digital divide equity issues. They were surprised to learn that white families were twice as likely to have two-way communications with teachers during pandemic school closures than Black and Latino families. Controlling for lack of connectivity, 60% of white families and students had frequent two-way communication with school personnel through phones, emails and conference platforms, while only 30% of Black and Latino families had such communication.

This example reflects a trend across the South and points to equity and authentic engagement issues between schools and families far deeper than the digital divide.

Strategy: Add or Bolster Two-Way Communication Methods

Schools can be proactive in delivering information to parents and caregivers in a manner that enables families to provide real-time feedback about their concerns. For homes with ample connectivity and devices, schools can use email for interactions beyond just sending out news. First, parents and caretakers need to know they are corresponding with a specific person. Second, the educator should be ready to respond quickly and participate in a peer conversation.

Educators must be prepared and supported to engage in dialogue in the dominant language spoken in the home and in a way that is culturally appropriate.

Fundamentally, communication should use tools that families have. The most common is the telephone, whether it be a landline, smart phone or flip-phone. Family members in south Texas told us they appreciated being able to talk with their child’s teacher by phone instead of having to figure out how to use higher-tech tools in the rare occasions they were available in the neighborhood or community center. They also reported that school personnel seemed to avoid talking with them by phone.

Provided families have access to Wi-Fi and devices, other tactics include setting up virtual office hours or town halls with live, real-time, online sessions. Weekly contacts and dialogues keep families informed and reduce the isolation brought about by the COVID-19 separations.

Schools can provide resources and institutional support for parent support specialists and other family liaisons ensure this contact happens. They also can retrain truancy officers to provide this support, too, rather than enforcing unhelpful and ineffective truancy measures.

Communicating with Purpose

No school communication method will build trust if it is not done in the spirit of partnership. Parents and caregivers are the experts on their children and youth. They know that the future of their community depends on the success of education today. Perhaps now more than ever, educators, students and families need to build strong relationships with each other in order to face the challenges of an isolating pandemic and its effects on education.

Youth Tech Mentors Bridge Schools and Families – Creative Community Responses to COVID-19 Webinar Recording

Partnering with Families to Reopen and Reimagine Schools – School Reopening Webinar Recording

Effective Family Outreach in the Pandemic Era, Article by Karmen Rouland, Ph.D., and Aurelio M. Montemayor, M.Ed.

September 9, 2020 Edition

Federal Court Strikes Down Department of Education Rule Requiring Public School Districts to Give More Relief Funds to Private Schools

The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia struck down last Friday a U.S. Department of Education rule that required many public school districts to give away more of their CARES Act emergency relief funds to private schools. The Court found that the Department’s interpretation of the CARES Act “equitable services” provision “conflicts with the unambiguous text of the statute” and is, therefore, void.

The decision in NAACP v. DeVos applies to schools nationwide. The plaintiffs are both school districts and families, including Broward County Public Schools, Fla.; DeKalb County School District, Ga.; Denver County School District, Colo.; Pasadena Unified School District, Calif.; and Stamford Public Schools, Conn., and families with children enrolled in public schools in Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Mississippi, Nevada, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington, D.C.

In a statement hailing the Court’s decision, attorneys for the plaintiffs noted the Department’s rule would have funneled “scarce public resources to private education, to the detriment of our highest-need students in public schools across the country.”

A coalition of Texas-focused educational equity organizations submitted an amicus brief in the lawsuit, citing IDRA’s research: Cutting Public School Funds to Subsidize Private Schools. The amicus brief stresses that the Department’s rule would divert those much-needed resources to private schools, regardless of their students’ family income. In Texas, the rule would have required 185 public school districts to set aside an additional $38.7 million in relief funds to private schools within their district boundaries.

Public schools need those relief funds (and more) to ensure safe and supportive schools for all students. Schools, families and students across the country have identified numerous needs during COVID-19, including for resources to address learning loss during school closures, narrow the digital divide, and improve important connections between schools and communities.

Every bit of relief funding is particularly important in school districts that were already struggling to serve students in families, like in Texas, where a large portion of federal funds are not being used for new COVID-19 costs, but to replace a portion of the state’s share of per-pupil attendance funds to which school districts are entitled. While many challenges to equitable funding persist, the Court’s decision last week ensures public school districts will be able to use more critical relief funds for their students.

Look up how much money each Texas school district would have lost (among those affected).

September 3, 2020 Edition

Texas-focused Education Equity Groups Support Lawsuit Challenging U.S. Department of Education Rule that Shifts Relief Funds from Public Schools to Private Schools

Advocacy groups, school districts and others across the country filed lawsuits against the U.S. Department of Education, challenging a new rule that requires some public school districts to use more of their CARES Act emergency relief funds to support private school students within their district boundaries. The lawsuits claim the Department’s rule ignores Congress’ intent that relief funds only be used to support private school students from families with limited incomes – a long-standing requirement for federal funds called “equitable services.” Instead, the new rule allocates more public funds to private schools based on total student population, regardless of family income.

Many organizations have filed amicus (“friend of the court”) briefs in the lawsuits, with several briefs citing IDRA’s recent analysis, Cutting Public School Funds to Subsidize Private Schools. The analysis shows the Department’s new rule could cost 185 Texas school districts a total of more than $44 million – an additional $38.7 million more than they are required to use for private school services under the normal rules.

In the amicus brief filed by the coalition of Texas-focused educational equity advocates, the groups argue the Department’s new rule unlawfully replaces the equitable services distribution methods Congress intentionally adopted in the CARES Act.

Additionally, the groups point to the detrimental impact the Department’s rule will have on students of color and students in Texas schools that have been historically underfunded and underserved. Citing projected revenue shortfalls and decades of funding equity battles in the courts and legislature, the groups argue the rule “will further exacerbate existing educational inequities by depriving Texas public school districts of funds desperately needed to keep school communities safe and provide critical education services.”

For more information see the amicus briefs by the Council of the Great City Schools in State of Michigan, et al. V. DeVos and the coalition of Texas-focused educational equity advocates in NAACP v. DeVos. At the time of writing, federal judges in Washington and California had issued preliminary injunctions blocking the Department of Education from enforcing its rule in several states.

August 26, 2020 Edition

Family Engagement is Key to Student Safety Amidst COVID-19 Reopening

Over the summer, state and local school leaders throughout the U.S. South have wrestled with decisions about whether to open schools in-person, remotely or some combination. Many emphasized in-person instruction as the way forward.

For example, Florida’s Education Commissioner issued an emergency order requiring all schools to offer the option for learning in person at least five days per week. Similarly, South Carolina’s State School Superintendent published guidance that required schools to offer the option for students to receive in-person instruction while stopping short of mandating five days a week.

State-level education leaders in most other Southern states left the decision to local districts, but have recommended that districts mix remote and in-person instruction (see links at the end of this article). Many of the decisions about how a child will attend school has been left up to students’ families. Thus, it is vital for schools to provide families and parents with up-to-date information about how students and school staff are being impacted by the pandemic.

COVID-19 conditions across the South have constantly shifted. Schools that opened for in-person instruction struggle to stay open. Although schools have been open for just a few weeks, at least one school has had to close temporarily due to COVID in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina and Tennessee.

Although the full scope of infections in student populations is difficult to determine due to limited testing, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that infection rate in children 17 and under increased “steadily” from March to July while students were largely out of school. With children coming into closer proximity in school, the number of COVID-19 cases and school closures may rise as more students across the South head back to school.

Understanding the current status of the pandemic is especially important for families of color as the CDC notes that “long-standing health and social inequities have put many people from racial and ethnic minority groups at increased risk of getting sick and dying from COVID-19.”

State education leaders must communicate up-to-date information about the pandemic to enable families to make the best decisions for their students. Several states in the U.S. South region are reporting data of this type.

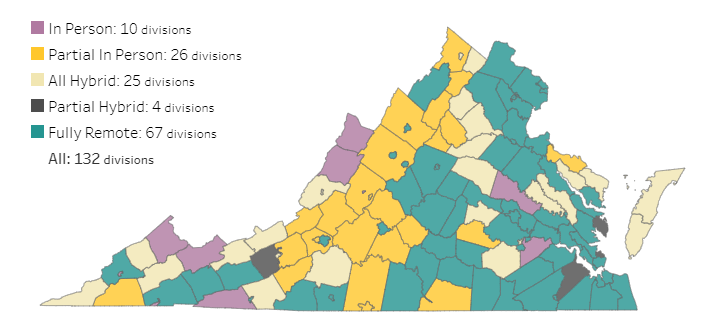

Snapshot Map: How Virginia Schools Are Reopening

The Virginia Department of Education published an interactive county level map that details the kind of instruction that parents can expect.

The Tennessee Department of Education created a dashboard that provides the instructional model in each school district.

The North Carolina Department of Public Health publishes a bi-weekly report of clusters of outbreaks in child care and school settings.

The Arkansas Department of Health similarly publishes numbers of COVID-19 cases by school district.

Recognizing the need for more transparency, education leaders in Texas and Louisiana recently announced plans to create statewide tracking databases for cases that arise in schools. These data tracking systems are a necessary addition to local communication from school districts to families when there is an outbreak in a local school. These systems help identify which safety practices best protect students and staff.

But in order to keep students and families safe during the pandemic, school leaders must do more to equip families with timely information for making the safest decisions possible for their students. We recommend that schools consider the following.

- Increase resources for parent support specialists who are tasked with ensuring consistent communication with families. Liaisons should speak the language of families the school serves when possible. For more staff, schools can repurpose school truancy officers (who should be instructed not to enforce punitive consequences when students are absent from virtual or in-person school).

- Provide low-tech options for families to remain engaged with their schools, including phone trees, text alerts and similar outreach strategies.

- Ensure all materials, including remote learning platforms, are available in families’ home languages.

- Collect surveys frequently – using multiple distribution and collection modes – to facilitate hearing and addressing emerging needs of families quickly.

-

- Increase funds for racially and ethnically diverse, high-quality counselors, social workers, and other mental and behavioral health professionals. Resources can be diverted from standardized testing and school policing budgets to hire these personnel.

To learn more about IDRA’s family leadership in education model and how to start strong school-family student partnerships, check out IDRA’s family engagement resources. For more information about ensuring equity in school reopening processes, review and share IDRA’s equity in reopening infographic.

__________________________________________________________________________

*See reopening plans in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

August 12, 2020 Edition

An Equity-focused Plan for Reopening Schools Safely

School reopening policies must be responsive to the needs of all families, students, teachers and schools. To ensure equity as schools reopen, IDRA makes the following policy recommendations to state, higher education, and school district leaders, including students and families. For a printable, sharable infographic, check out our equity checklist below.

See our full list of recommendations to ensure equitable educational opportunities for students in the immediate- and long-term in our online guide, Ensuring Education Equity During and After COVID-19.

1. Additional funds and resources should be channeled to face pandemic-related issues.

* Funnel CARES Act and other federal stimulus funding toward the K-12 settings that serve high populations of marginalized students.

* Invest in additional mental health professionals, including counselors and social workers. It is more important than ever to achieve recommended ratios and even go beyond in order to address the unique trauma and needs of students, families and school staff. Additional professionals can help to maintain contact with families during school closures.

* Ensure emergency funds (state and federal) are used to address schools’ virus-related needs that arise and supplement not supplant basic education funding. School districts that do not have additional resources to address unanticipated COVID-19 related needs should be not penalized with a subsequent funding shortage.

2. School districts should develop support systems for students’ academic, social and emotional needs.

* Develop small committees that include a counselor, social worker or family liaison who can ensure that the particular social circumstances of the family are taken into account in some way when determining the needs of the student.

* Expand use of formative assessment systems (such as individual graduation committees in Texas). Formative assessments measure student progress over time and consider a variety of factors to determine course mastery.

* Involve families and other stakeholders in decisions about uses of funds through surveys, meetings, etc. Use family support specialists for this purpose.

* Encourage peer-to-peer mentoring and cross-age tutoring programs among students. These programs can encourage community bonds while using young adults’ digital skills to build academic relationships. Programs can be monitored by teachers and other educational personnel.

3. Educators should maintain high academic expectations for students that prepare them for college admission, enrollment and success.

* Work together with K-12 schools and institutions of higher education to heighten college counseling and enrollment information for students and families. Schools should provide clear online information and communications about college admission requirements, instructions for obtaining transcripts and teacher letters of recommendation, COVID-19-related adjustments, and resources for seeking financial aid and scholarships.

* Develop, refine and maintain open platforms of communication with students and families to alleviate confusion and be responsive to emergent needs and concerns. Online platforms should be coupled with robust in-person outreach, particularly with families and students that districts have struggled to reach.