English learners have the civil right to access excellent educational opportunities that ensure English mastery while honoring and supporting their home languages and cultures.

English learners make up nearly 20% of the Texas public school student population – over 1 million students. They are hurt by a number of policies and practices, including a lack of funding, shortages of qualified instructors, and incomplete data reporting about their progress and needs.

English learners make up nearly 20% of the Texas public school student population – over 1 million students. They are hurt by a number of policies and practices, including a lack of funding, shortages of qualified instructors, and incomplete data reporting about their progress and needs.

Some Texas Policies Hurt English Learner Students

Fair funding, early education and protections for immigrant students affect English learner (or emergent bilingual) students.

Research shows that schools should receive an additional 50% in per-pupil funding to provide equitable supports and services to emergent bilingual students (IDRA, 2015). However, Texas only provides an additional 10% for emergent bilinguals – one of the lowest rates in the country (Education Commission of the States, 2014; Latham Sikes & Davies, 2019).

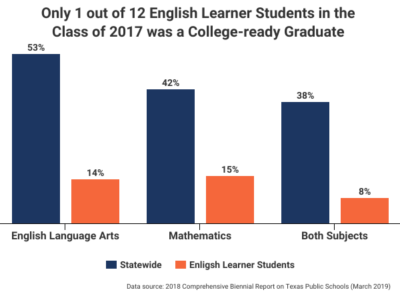

As a result, schools are ill-prepared to serve emergent bilinguals: Emergent bilinguals are among the students most likely to drop out, have lower rates of college readiness, and have limited access to high-quality certified teachers (Johnson, 2016). Texas has faced a persistent shortage of certified bilingual and ESL teachers (U.S. Department of Education, 2017).

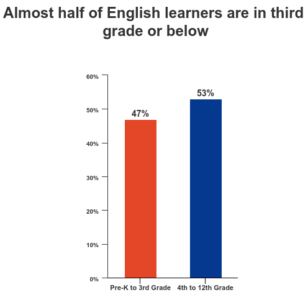

Only about half of Texas emergent bilinguals are enrolled in pre-kindergarten to third grade (PEIMS, 2019). Policies on pre-K, early literacy and early childhood education significantly impact emergent bilinguals’ educational opportunities. The state still has not funded full-day pre-K for school districts and does not maintain strong data on emergent bilinguals’ early education opportunities. This leaves us in the dark about emergent bilinguals’ full educational experiences and successes.

Only about half of Texas emergent bilinguals are enrolled in pre-kindergarten to third grade (PEIMS, 2019). Policies on pre-K, early literacy and early childhood education significantly impact emergent bilinguals’ educational opportunities. The state still has not funded full-day pre-K for school districts and does not maintain strong data on emergent bilinguals’ early education opportunities. This leaves us in the dark about emergent bilinguals’ full educational experiences and successes.

Current attacks on immigrant families also affect emergent bilingual students. While the vast majority of emergent bilinguals are born in the United States, their language designation often gets confused for their citizenship status (MPI, 2018). Any attempts to marginalize students based on their actual or presumed citizenship status violates their civil rights, per Plyler v. Doe (1982). By law, public schools cannot inquire, track or discriminate on the citizenship status of students or their families.

How does House Bill 3 affect emergent bilinguals?

In 2019, the Texas legislature passed House Bill 3, which changed how schools across the state are funded. HB 3 changed funding for emergent bilinguals by:

In 2019, the Texas legislature passed House Bill 3, which changed how schools across the state are funded. HB 3 changed funding for emergent bilinguals by:

- increasing the basic funding for every Texas student;

- creating additional funding for schools serving emergent bilinguals in kindergarten through third grades (though schools are not required to use this funding for emergent bilingual students and can instead use it to fund pre-K programs); and

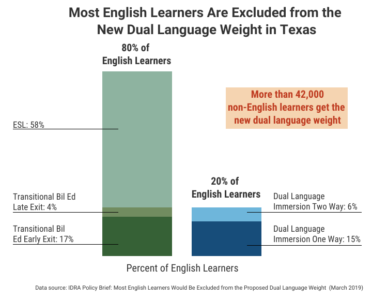

- establishing additional funding for educating emergent bilinguals and other students in dual language programs (at a little more than $300 per student). Unfortunately, 80% of Texas emergent bilinguals attend schools that do not offer dual language programs, so they cannot benefit from this change in the law.

Even with some increases in funding, there are still not enough resources for educating emergent bilinguals.

See new report, Creating a More Bilingual Texas, coauthored by IDRA and Every Texan.

Policy Recommendations for Texas

The Texas Legislature should…

- Change statutory language for “English learners” to “emergent bilingual” students to prioritize importance of bilingualism over an English-only focus.

- Create a statewide plan for equitable education for emergent bilingual students.

- Require school districts to spend at least 90% of their bilingual education funds on direct costs for emergent bilingual students in the classroom.

- Increase funding for emergent bilingual education in all types of instructional programs not just for specific programs like dual language.

- Support expansion of dual language programs, which currently serve only one in five emergent bilingual students.

- Increase the number of certified bilingual education teachers at all grade levels and address ESL-certification shortages.

- Support school districts to identify ways to address teacher shortages without relying on waivers that allow under-qualified teachers to serve emergent bilingual students.

- Support development of a paraprofessional pipeline and grow-your-own programs to encourage people to become bilingual education teachers in their communities.

- Collect and report data on the number of students who graduate bilingual or multilingual through the Seal of Biliteracy. In districts where it is offered, the Seal of Biliteracy designates students who have become bilingual and biliterate across academic subjects.

- Create a state broadband and technology plan that serves the needs of emergent bilingual students and engage families and community stakeholders throughout the plan.

- Pause accountability requirements for assessments for spring 2021, such as Texas English Language Proficiency System (TELPAS) tests. Use TELPAS as a formative assessment to collect quality data about student learning and progress.

The state and local districts should…

- Prioritize bilingual/ESL education at-home instruction resources, tools and supports for families during COVID-19. Instructional materials to families should be in parents’ preferred language according to school records.

For more information, contact Dr. Chloe Latham Sikes, IDRA Deputy Director of Policy (chloe.sikes@idra.org) or Ana Ramón, IDRA Deputy Director of Advocacy (ana.ramon@idra.org).

References

Craven, M. (April 2019). Current Proposals for Texas’ Investment in English Learners Still Not Enough. IDRA Newsletter. https://www.idra.org/resource-center/current-proposals-for-texas-investment-in-english-learners-still-not-enough/

Education Commission of the States. (May 27, 2020). 50-State Comparison: English Language Learners, website. https://www.ecs.org/english-language-learners/

Grayson, K. (March 2018). Schools’ Duty to Education English Learner Immigrant and Migrant Students. IDRA Newsletter. https://www.idra.org/resource-center/schools-duty-to-educate-english-learner-immigrant-and-migrant-students/

IDRA. (2015). IDRA José A. Cárdenas School Finance Fellows Program 2015 Symposium Proceedings – New Research on Securing Educational Equity & Excellence for English Language Learners in Texas Secondary Schools. San Antonio, Texas: IDRA. http://www.idra.org/images/stories/Proceedings_FullPub_06052015.pdf

Johnson, R. (February 10, 2016). Texas Must Seize the Opportunity to Improve the Education for English Language Learners – Testimony before the Texas Senate Education Committee. IDRA. http://www.idra.org/images/stories/TX_Must_Seize_the_Opportunity_to_Improve_the_Ed_for_ELL_021016.pdf

Latham Sikes, C., & Davies, W. (April 22, 2019). Building Equity in Bilingual Education School Finance Reform in Texas: Context and Importance of the Problem. Austin, Texas: Texas Center for Education Policy. http://tcep.education.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Sikes-Davies-TCEP-Policy-Brief-4.22.19-FINAL.pdf

Migration Policy Institute, (2018) “English learners in Texas.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/EL-factsheet2018-Texas_Final.pdf

Robledo Montecel, M., & Cortez, J.D. (Spring 2002). Successful Bilingual Education Programs: Development and Dissemination of Criteria to Identify Promising and Exemplary Practices in Bilingual Education at the National Level, Bilingual Research Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ647787

Robledo Montecel, M., Cortez, J.D., Cortez, A., & Villareal, A. (2016). Good Schools and Classrooms for Children Learning English: A Guide. San Antonio, Texas: IDRA. https://www.idra.org/publications/good-schools-classrooms-children-learning-english-guide/

TEA. (March 25, 2019). EL Student Reports by Category and Grade, 2018-2019. Austin, Texas: Texas Education Agency.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017). Teacher Shortage Areas Nationwide Listing, 1990-1991 through 2017-2018. Washington, D.C. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ope/pol/bteachershortageareasreport201718.pdf