• Nilka Avilés, Ed.D. • IDRA Newsletter • September 2018 •

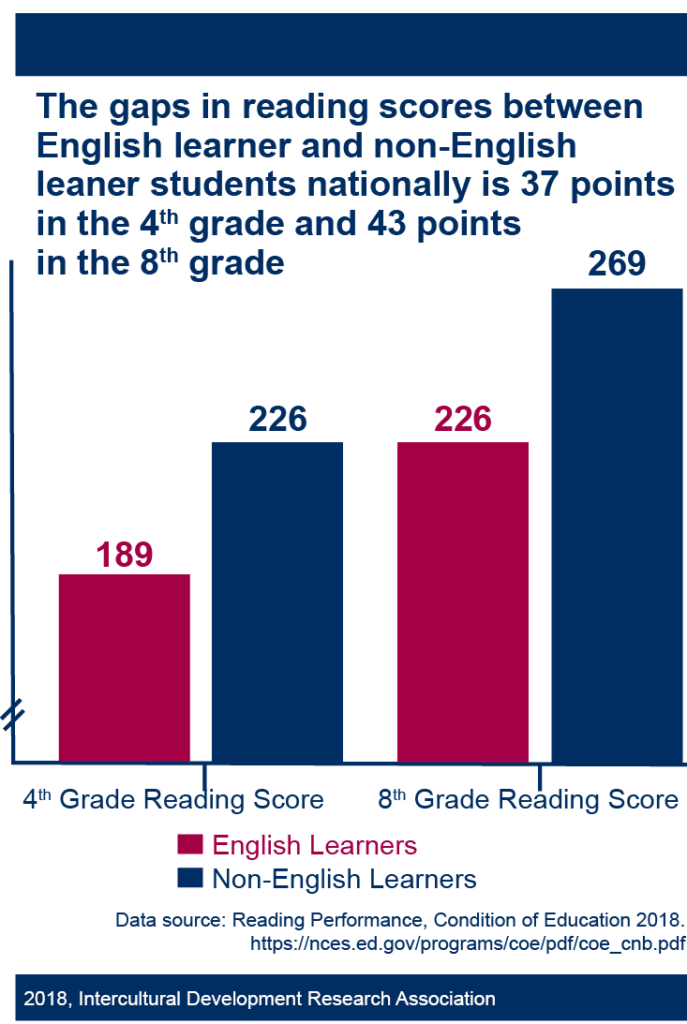

In an era of rapid educational changes and dynamic diverse student populations, educators and transformational leaders must deeply reflect on how they are narrowing opportunity gaps. This includes making sure our schools provide English learners (ELs) a quality education that honors and builds upon the literacy skills in their home language and develops a highly sophisticated level of literacy in English.

In an era of rapid educational changes and dynamic diverse student populations, educators and transformational leaders must deeply reflect on how they are narrowing opportunity gaps. This includes making sure our schools provide English learners (ELs) a quality education that honors and builds upon the literacy skills in their home language and develops a highly sophisticated level of literacy in English.

Through the work of our School Turn-Around and Re-energizing for Success (STAARS) Leaders project in a school district in San Antonio, IDRA found some implementation practices that proved to be very effective in increasing leader and teacher capacity and effectiveness in improving literacy for ELs. This article cites a key study because of the significant number of participating ELs involved. Findings led to the creation of professional development activities that address a critical reading skill that likely contributed to the high number of students who had been failing to succeed in state assessment tests.

Building Student Inferencing Skills Tips the Scales

Researchers at IDRA analyzed data for multiple campuses focusing on the third grade state assessment and curriculum standards in reading. We found that around 90 percent of the test questions relied on some type of inferencing. Conducting a vertical analysis of the Texas curriculum standards revealed that inferencing is a skill that is required starting in pre-kindergarten and going all the way to 12th grade. Overall, most students, including ELs, did poorly in inferencing on the state assessment test. We identified that there was a big disconnect between the curriculum, the assessment and the instructional program. This was true of all student groups involved in the study.

The research literature indicates that a key indicator in the ability to draw inferences predetermines reading skills. There is a strong correlation between inferencing and comprehension. If students cannot infer effectively, they are not able to comprehend effectively (Kispal, 2008).

In disaggregating the data for the schools we studied, we saw variation by classroom in how students performed on reading assessments. We met with the school principals to review the analysis and findings. Through reflective practices, the principals decided to focus on strengthening teacher capacity in building inferencing skills into their literacy programs. At the same time, this process helped teachers increase their content knowledge, thereby improving their overall quality of teaching and learning.

In disaggregating the data for the schools we studied, we saw variation by classroom in how students performed on reading assessments. We met with the school principals to review the analysis and findings. Through reflective practices, the principals decided to focus on strengthening teacher capacity in building inferencing skills into their literacy programs. At the same time, this process helped teachers increase their content knowledge, thereby improving their overall quality of teaching and learning.

We interviewed teachers about their work to increase literacy skills, and many shared their poor preparation in their pre-service teaching programs. They also expressed the need to know effective classroom inference-focused strategies. In consultation with school leaders, IDRA provided customized professional development through five modules focused on inferencing and reasoning skills.

At the same time, teachers and school leaders determined which formative assessments to give and how often. Those results were analyzed and discussed within their professional learning communities to develop action plans to ensure instruction was aligned with the state curriculum standards and the state assessments. Lessons, then, strategically targeted both the standards and the assessments.

Using the explicit model of instructional delivery, inferencing using metacognition was intentionally taught, stressing the importance of developing thinking processes to become habits of the mind. The “end in mind” was to develop strategic thinkers who can meet college and career readiness standards.

Teachers used what they had learned in training sessions with principal support for intensive small-group interventions focusing on different types of inferencing along with metacognition practices. Emphasis was placed on developing academic language and thinking processes in all content areas.

During professional learning community sessions, teachers reviewed and analyzed the data, and they used the data to inform their instruction. They worked as a team in lesson development, delivery, and monitoring the progress of the students in order to move them into higher proficiency levels. Teachers and leaders tracked students’ growth to consistently guide students in improving their learning.

By having this strong focus on intentional teaching and learning results, the schools improved literacy scores and helped close the achievement gap between EL and non-EL students. They also were moved out of the “needs improvement” rating and received awards for distinction.

Transformational Leaders Create a Focused Environment

This example demonstrates that for school leaders to be effective with EL policies and implementation strategies, they must value students, believe in their potential success, build teachers’ content knowledge, and implement strong instructional programs with genuine support systems and resources. Leaders must use a social justice lens to build a culture dedicated to equity and excellence for all students beginning with developing literacy (Avilés, 2016).

Research by Stepanek & Raphael (2010) reinforces the need for school leaders to face two major questions:

- How do we create a culture of urgency and a focus of high standards and expectations for teachers to implement evidence-based instructional practices that will improve EL linguistic and academic achievement?

- What does it take for a transformational leader to establish a school culture dedicated to engaging ELs and improving literacy and student success for ELs as well as for all students?

First, transformational leaders must support, articulate and advocate for student rights and respect for cultural and linguistic differences. Leaders must first define and establish operational norms that are asset based and grounded on a philosophy that “all students are valuable; none is expendable.”

For ELs, this means recognizing that they have a language, culture and experiences that form the foundation for their learning. Leaders and teachers must foster a nurturing and positive approach, one that embraces and recognizes their strengths and “funds of knowledge” that will contribute to EL engagement in their own educational growth.

Second, leaders and staff must have a shared vision of success for all children. Everyone must be committed, inspired and accountable to improving instruction along with delivering genuine support services. This vision is one in which all students meet high standards. The transformational leader communicates the vision and its direction and provides the support and resources for all teachers to ensure that there is an ongoing monitoring process for improvement.

Third, leaders can improve teacher practice through targeted professional development and cognitive coaching. They can increase student performance by developing a growth mindset and school culture to support asset-based instruction. For example, when students struggle, educators advocate Carol Dweck’s concept of “not there yet,” giving students the time and support to master the required content knowledge. Their talents and potential can be nurtured through refining their efforts and supporting a determination to excel. Thus, all students establish learning goals, become cognizant and more accountable of their own learning, and monitor the rate of intellectual growth.

Listen to our podcast episodes on A Principal on Leadership for a Turnaround School – Part 1 –Episode 168 and Part 2 – Episode 169

Instructional leaders must have an unwavering commitment to sustain systemic change to ensure student success for all. If you are this visionary transformational leader, you will compellingly contribute to the creation of innovative systemic changes that will ensure the academic success all children deserve.

Resources

Avilés, N. (November-December 2016). “Fostering Excellence Through Social Justice Principles in Schools Serving English Learners,” IDRA Newsletter.

Farnam Street. (2018). “Carol Dweck: A Summary of the Two Mindsets and the Power of Believing that You Can Improve,” Farnam Street blog.

Herrera, S., Truckenmiller, A.J., & Foorman, B.R. (September 2016). Summary of 20 Years of Research on the Effectiveness of Adolescent Literacy Programs and Practices (REL 2016–178). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast.

Grayson, K. (November-December 2016). “School Leadership: Transforming to Lead Linguistically Diverse Student Populations,” IDRA Newsletter.

Kispal, A. (2008). Effective Teaching of Inference Skills for Reading Literature Review. England: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Mind Tools. (No date). “Kotter’s 8 Step Change Model: Implementing Change Powerfully and Successfully,” Mind Tools website.

Song, K.H. (2016). “Systematic Professional Development Training and Its Impact on Teachers’ Attitudes Toward ELLs: SIOP and Guided Coaching,” TESOL Journal, 7(4), 767-799.

Stepanek, J., & Raphael, J. (2010). “Creating Schools that Support Success for English Language Learners,” Education Northwest, 1(2) 1-4.

Nilka Avilés, Ed.D., is an IDRA senior education associate and co-directs IDRA’s Re-Energize project. Comments and questions may be directed to her via email at nilka.aviles@idra.org.

[©2018, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2018 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]